Skin problems can affect almost any horse anywhere, whether you live in a tropical climate with year-round heat and humidity or are preparing to start blanketing your pony against autumn rains and winter snow. Luckily, most are straightforward to treat—but it’s helpful to know whether your horse’s particular issue is caused by bacteria, fungus, virus, or an allergic reaction. We got the skinny—plus some treatment and management tips—from Dr. Luke Fallon at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute.

Rain Rot – Caused by bacteria

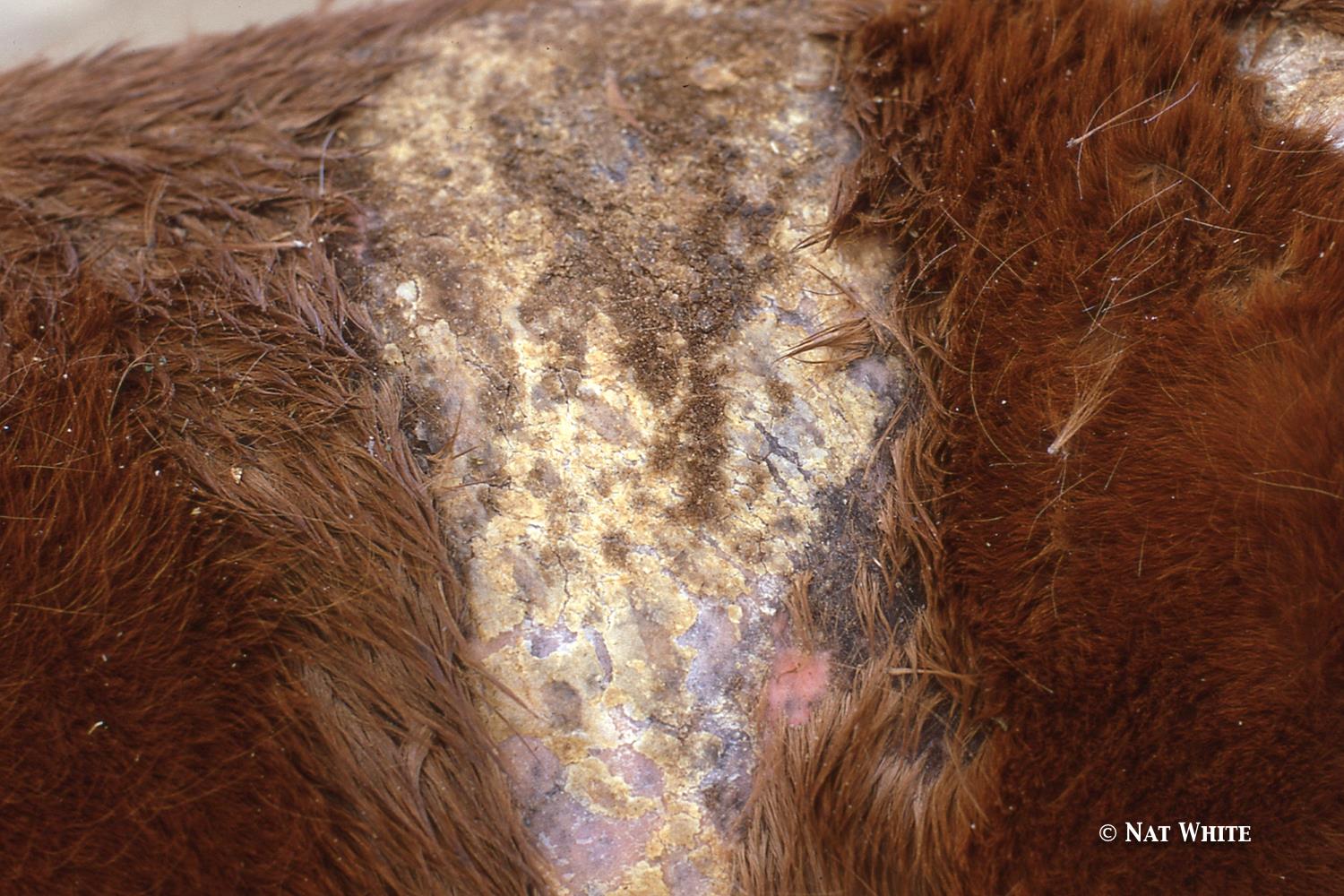

“You’re most likely to see rain rot start somewhere along the top line, from the withers all the way back to the tail head,” said Fallon. “It may occur along the shoulder and neck region, too, and it typically will have a miliary appearance, which just means that it’s dispersed in a bunch of crusty or scab-like lesions, in sort of a shotgun pattern.”

Bacteria causes rain rot, but that doesn’t mean you need to reach for antibiotics immediately.

“Typically, you can pick off or debride those scab-like lesions, and I find that it’s better to do that, followed by treating the horse’s skin topically with a medicated shampoo, which can then get directly to the area that needs to be treated,” Fallon said.

Medicated shampoo isn’t the only weapon in the arsenal against rain rot. “I’ll often treat those horses not only with medicated shampoo, but we also use lime sulfur or a shampoo with lime sulfur and captan that also has soothing aloes in it,” Fallon said. Also good: shampoos that contain iodine, betadine, or chlorhexidine.

“Betadine scrub is great because it’s an antimicrobial,” Fallon added. “Leave it on for 10 to 15 minutes, and then wash it off completely, always being careful around the horse’s eyes.”

If the horse is sensitive and objects to having the scabs peeled, scraped, or scratched off before shampooing or another topical treatment, Fallon has some suggestions for softening the scabs to make them easier to remove.

“You might be better served to treat the horse topically with shampoo and wait after a treatment or two before you tackle the lesions,” Fallon said. “If you do two or three bathings, a lot of times you’ll take that soreness out of the scabs and you can go on and debride them away.”

Another hint: apply baby oil directly to the scabs for a day or two before attempting to remove them during a medicated bath. (If your horse is troubled by dew poisoning—another form of dermatitis also known as scratches—on his pasterns or fetlocks, bandaging over a medicated salve or cream can also make it easier to remove the scabs or hyperkeratosis.)

Rain rot can occur at any time of year, and, despite its name, its appearance doesn’t necessarily have to do with a prolonged period of wet weather.

“Most often, it is associated with wet weather, but I’ve also seen it in dry times,” Fallon explained. “I’ve also seen it on horses that are overblanketed, when there’s too much moisture trapped underneath the blanket and the hair coat isn’t getting to dry out or allowed exposure to light.”

That’s one reason it’s so important to make sure your horse is completely dry before tossing on a blanket.

“Beyond making sure you’re blanketing appropriately, you also want to maintain a healthy hair coat,” said Fallon. Here are a few tips to help prevent rain rot:

- Never share brushes or blankets between horses.

- Disinfect brushes regularly (for tips of the best way to disinfect brushes, buckets, and stalls, see this Equestrian Weekly article).

- If your horse has sweated excessively, even if he’s only been standing in his paddock, bring him in, let him dry off, and bathe him to get rid of the irritating salty residue.

- Keep your horse’s blanket cleaner than you keep your own barn coat!

- Give a preemptive antimicrobial bath if horses around yours are coming down with rain rot.

In more severe cases, your veterinarian might need to prescribe systemic antibiotics.

“Typically, if they’re very irritated or if there’s a lot of pus underneath when you pick off those scabs or crusts, I’ll quite often put them on something, such as sulfa drugs,” Fallon said. “Used with the shampoo, that will typically kill the bacteria.

“If it’s severe enough that you think the horse might need antibiotics, then I recommend having the vet look at it,” Fallon added. “You might not need to put the horse on systemic antibiotics, and you don’t want to encourage antibiotic-resistance in your barn or your herd. If you can get away with treating it with just antiseptic soaps, you’re better off.”

Less serious cases with smaller, more dispersed scabs typically resolve with topical treatments alone in a week or 10 days, said Fallon.

Ringworm – Caused by fungus

Ringworm’s name is misleading: it’s caused by a fungus, not a worm. Like other skin diseases, it can spread easily from horse to horse, but ringworm also can pass from horse to human—so good hygiene when handling an affected horse is a must.

Where rain rot typically has a scattered appearance, ringworm lesions are usually more distinct patches of raised skin, often round, which have lost hair and can become scaly or crusty.

Ringworm isn’t uncommon in populations of younger horses, like weanlings and yearlings, but it can also affect horses in training, where it sometimes begins at the site of a girth rub or other places where tack has chafed the skin.

“It doesn’t always present itself as a circular lesion,” Fallon noted. “I’ll sometimes see it where a horse will shed out all over a large portion of their face or neck. If it’s on the flank or hindquarters, it’s typically a more well circumscribed shape that can vary from the size of a dime up to silver dollar-sized raised plaque. They’re often very sore, and they can crop up overnight. The whole plaque or affected area will come off.”

The treatment for ringworm is much the same as for rain rot, and, in fact, many of the antimicrobial shampoos—including those that combine lime sulfur and captan (captan is a fungicide)—on the market today will work for both. But you do want an antifungal component to your treatment if the diagnosis in ringworm, Fallon said.

“There are some topical antifungal shampoos that contain miconazole or itraconazole, too,” he added. “A lot of times people want to treat it systemically with antifungals, but I find that, by and large, by the time you treat them systemically, the topical treatments probably would have been as effective as treating them systemically.”

Systemic antifungals, which can be administered orally or intravenously, also can have some side-effects. They can affect liver and kidney function and can cause changes in behavior and appetite. “These are things to consider when using systemic antifungals, so please consult your vet,” Fallon said.

Keeping tack clean and disinfected—and not sharing these items between horses—can help prevent the fungus from spreading.

“If your horses are sharing brushes, you’ll see that ringworm run right through the barn, if you’re not careful,” Fallon cautioned.

Hives – Caused by allergen

A horse can get hives for a variety of reasons, from an insect bite to a contact or food allergy. And while hives aren’t a true skin disease, they’re worth mentioning here partly because they can be hard to distinguish from rain rot or other skin problems.

“There can be a lot of edema [swelling] with ringworm when it first pops up, too,” said Fallon. “I’ve had experienced horse owners or managers tell me, ‘I don’t know whether we’ve got hives or ringworm.’”

Hives are localized swelling, fluid-filled bumps that can break out in multiple sites on a horse’s body, “similar to what you get when you get stung by a bee or bitten by a mosquito,” Fallon said. “There’s typically not a scab associated with a hive unless it’s an insect bite. Hives will respond to antihistamines, anti-inflammatories, or steroids.”

The hives can get pronounced enough that they weep. “At that point, you probably should have the horse looked at,” advised Fallon, “because that’s a pretty severe reaction.”

“It’s a systemic allergy, and that can be due something they’re eating, something they’re inhaling, or some kind of insect bite,” Fallon explained. “It’s usually environmental. Did you just get new bedding in, for example? Think about where it’s occurring on the body, and that might lead you to the culprit. Is the horse turned out in a new paddock? Did you start him on new feed? Take into account what is new in the horse’s life or environment.”

Banamine and oral antihistamines can be the horse owner’s first line of defense, but, as always, be sure to call your veterinarian before medicating—and certainly get veterinary advice before administering steroids.

Warts – Caused by virus

Warts can sometimes appear around the muzzle or eyes, as well as in the ears, and while they aren’t necessarily a serious problem—unless they are located where the bit rests—they can be unsightly.

“Typically, it’s a papilloma virus that causes them,” Fallon explained. “You can treat them topically.”

Treatment generally involves getting your veterinarian to scrape the warts away, which causes them to bleed—and causes the horse’s own immune system to step up its response to the virus.

“Within about three weeks, they usually will shed the warts on their own,” Fallon explained.

Other topical treatments include glycerin or specialized anti-wart formulations.

Want articles like this delivered to your inbox every week? Sign up to receive the Equestrian Weekly newsletter here.

This article is original content produced by US Equestrian and may only be shared via social media. It is not to be repurposed or used on any other website than USequestrian.org.