“It is easy to conquer the world from the back of a horse” ~ Genghis (Chinggis) Khan

Ask someone who their favorite teacher is, and their response will probably be a human. For me, horses have fulfilled the role of invaluable mentors. Horses teach us responsibility and to prioritize taking care of what’s

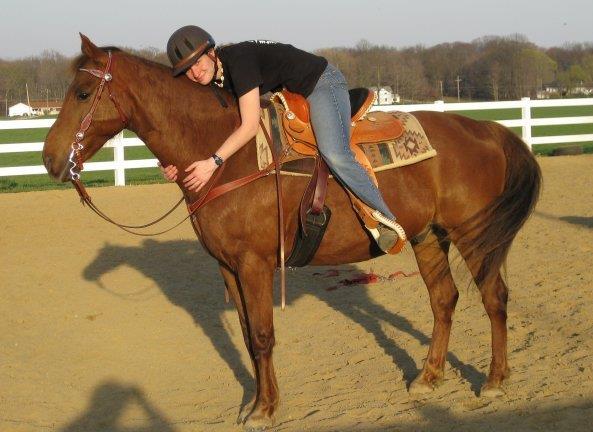

Photo: Courtesy of Katey Duffey

more important than our own needs. They teach us respect, because without it, there can be no growth of trust. Horses teach us we must relax when anxiety threatens to derail our progress. As large prey animals, horses teach us caution to prevent complacency. Horses also teach us how not to be intimidated by anyone who tries to make us feel inferior.

I began riding when I was six at a YMCA camp not far from my home in Canton, Ohio. Weekly riding lessons and summer ranch camp dominated my childhood. When I was 12, I dedicated every weekend, holiday break, and summer for several years as a ranch hand and trail guide, and to schooling new horses. The dozens of horses I had the privilege to work with became my teachers who instructed me how to be the best version of myself.

In 1998, the camp acquired a foundation Morgan that had been abused. I would’ve thought someone was crazy if they told me that the ill-tempered, dappled chestnut trying to kick my head off and bite my face would become my inseparable partner for over two decades. Unfit for the public program, Maximus (“Max”) became my staff horse and tolerated very few coworkers. I reveled in the challenge of working with the high-strung horse. However, he couldn’t remain a staff horse forever, so I bought him in 2003 to ensure he would never go to a slaughter auction.

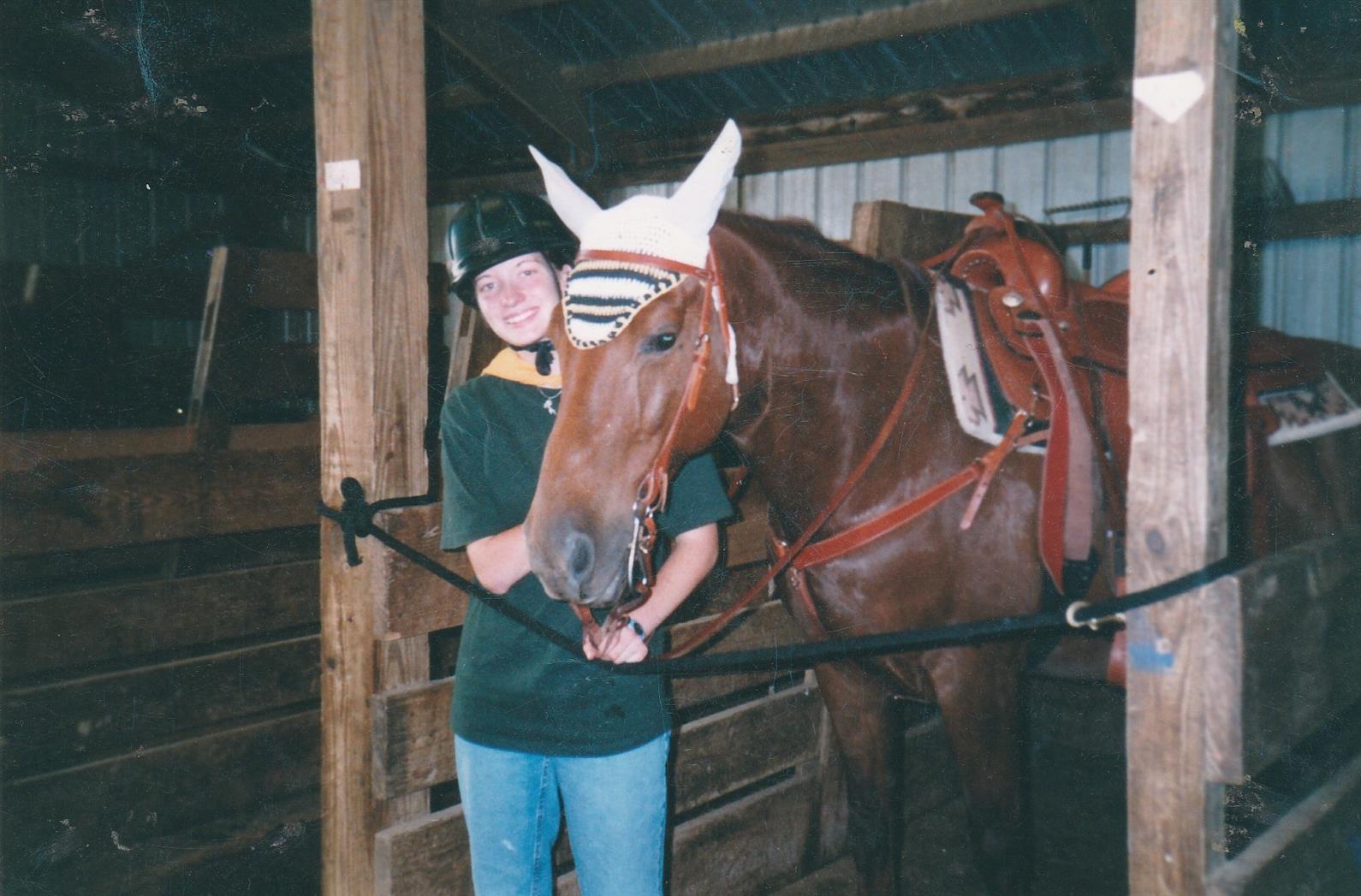

Max was part of the major milestones of my life, teaching me to push beyond my limits and try new things. We got to know each other through my transition in and out of high school, when he somehow broke a coffin bone before I left for Army Basic Training in the fall of 2003, and after I returned home in the spring of 2005 after a year in Iraq. Max was my support all through college and graduate school. Our bond grew immensely, as Max was my best friend who saved me from myself just as I saved him in his early years.

He transformed into a gentle, protective companion. Patience and a lot of creativity built a storybook relationship that has been applied to everything I’ve done.

After returning from Iraq, I had a lot of issues controlling my temper and anxiety. I was in a very dark place

Photo: Courtesy of Katey Duffey

mentally. I didn’t feel like I fit in with friends and family, and I was often isolated from them as I battled my demons alone. Max gave me a purpose to focus on, because he needed to be schooled after a long rest in a box stall and small turnout areas. Since Max was naturally spirited and had a ton of built-up energy from a year-and-a-half of healing from his injury without me around, I had to force myself to remain calm around him. He was my escape and acted as my “therapist” throughout every other stressful event when I thought the world was crashing down or just needed a neck to hug after a bad day. I’ve always heard that a high-strung rider should not pair with a high-strung horse, but Max and I somehow made it work. We each always knew what the other was thinking or feeling as second nature, and we instinctively made adjustments.

My ability to persist through the challenges in my chosen career path of wildlife conservation can be traced to my founding lessons working with horses. Along the way I’ve had dozens of falls, but thanks to growing up as an equestrian, I always forced myself to get back up and try again. Figuring out how to organize and implement a project is similar to working with a spirited mount. Conservation requires empathy and the willingness to make adjustments to how you go about your methods in order to adapt to things you can’t control.

Inevitably, the time that all horse owners dread comes. Max suddenly became very ill in July 2018 and rapidly began to deteriorate within only a month. It was a massive shock, but I couldn’t let him suffer. He was never one to give up, but eventually the effects of a fast-acting liver cancer took their toll. It was then that Max had one more lesson to teach me: that it’s okay to let go when our time in this world comes to an end. It was my final responsibility to him to help him rest with his dignity intact.

Photo: Courtesy of Katey Duffey

We had a tranquil last morning on August 14. There was a clear sky, and Max grazed as much as he wanted among the shady fruit tree grove. He was groomed and fed treats a final time while I recounted our adventures, until I led him under his favorite apple tree to cross over the Rainbow Bridge. It seemed he knew it was goodbye. Although standing proud with ears erect, Max had a serene stillness in him from his trust in me as I said my heartbroken farewells, kissed his nose, and stroked his neck.

The loss of Max has shattered my soul deeply, but we were fortunate to have each other for 21 of his 29 years. Those memories will forever keep him alive wherever I go and pick me up in my darkest moments … I close my eyes and we are back at that camp where our journey began. I can hear the birds along the trail and the saddle creaking with each of Max’s steps. His ears swivel forward, then back to me as I talk to him. Just around the bend, we top a hill onto “Hawk Valley.” It is a place named after a pair of red-tailed hawks that nest there. Max knows I like to wait and accepts the slack on the reins for him to munch grass. I scratch his neck and breathe in the fresh air while looking down over the pond in the clearing below. The evening sun makes the leaves shine gold, and the breeze rattles the branches of the canopy. Max and I are just living in the moment. I hear the cry of a hawk, and, as one, Max and I look up to watch it effortlessly glide across the valley …

There’s a bittersweet nostalgia as I recall the past moments while being faced with the reality that my equine soulmate is gone. Yet, as I will myself to move on in a temporarily horseless lifestyle, I can almost feel him nudging his head against me, pushing me forward, while his gentle nickers linger as an echo on the wind.

While I am conducting snow leopard research in Mongolia, it is amazing to be immersed in a culture that stemmed from a life relying on horses. Horses were the reason that Chinggis Khan’s forces were able to overpower most of Eurasia. Mongolians have continued to use them as their form of transportation on roadless terrain and for herding livestock since 3,000 BC.

The culture’s history can be seen in the hundreds of feral horses across the steppe, horse races as one of the three top national sports, and the sacred drink of fermented mare’s milk, called airag. The country’s national instrument is the horse-head fiddle, which even incorporates the rhythm of a gallop and whinny sounds within the music.

When I step out of my ger (nomadic dwelling) on a freezing morning before the day’s fieldwork, I see my host take a warmed grain mash out to his horse and gently stroke its neck. The horse is young and fidgets anxiously at its tie line, but the herder holds a calm demeanor in handling it. It is never easy to immerse yourself in a completely different culture with a language you don’t speak, but horsemanship is a universal language among equestrians. This is the language I use when building a rapport with herders. Respect is gained simply by being able to ride their horses to assist in taking your host’s sheep and goats out to grazing.

Through my translator, I share stories of Max. I gain smiling nods of approval from people who understand the bond between horse and rider. They know what it takes to mold that over time and I blush as I’m offered a shot of vodka to honor Max.

To learn more about the Morgan breed, visit US Equestrian's Morgan page and the American Morgan Horse Association.

Want more articles like this delivered to your inbox every week? Sign up here to receive our free Equestrian Weekly newsletter.

This article is original content produced by US Equestrian and may only be shared via social media. It is not to be repurposed or used on any other website aside from USequestrian.org.

Katey Duffey was born and raised in Canton, Ohio. She served six years in the Army National Guard in a transportation unit, driving five-ton tractor-trailers and serving as a machine gunner. Katey served a year in Iraq, as well as during hurricane relief for Hurricanes Gustav and Ike. She has a B.A. in Zoo and Wildlife Biology and an M.A. in Zoology. Her current research focus is on snow leopards and One Health.