It is a dreaded disease in the horse world, even though it often isn’t fatal. Strangles—one of the world’s most commonly diagnosed contagious equine diseases, according to the American Association of Equine Practitioners—is feared because it’s highly contagious and can be carried by horses who have no apparent symptoms—and once it’s in a barn, it can be difficult to get rid of.

Photo: Stefan Walkowski

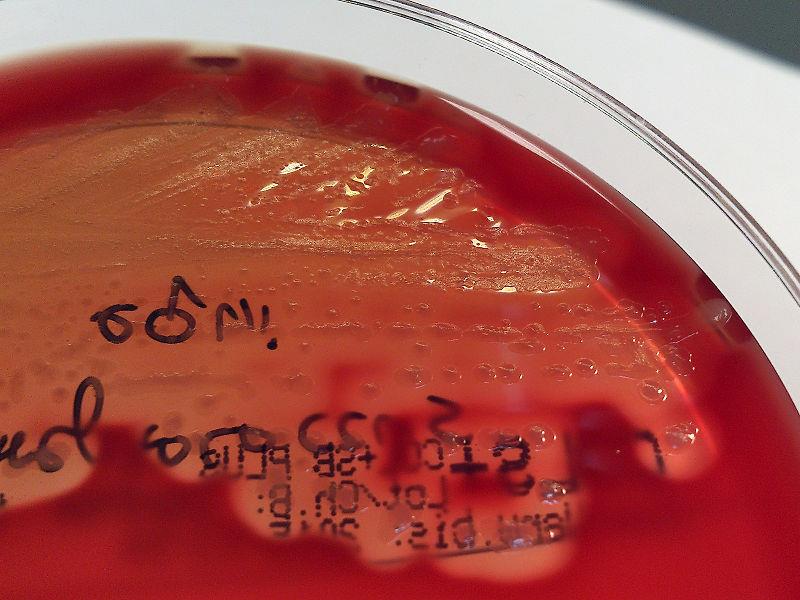

The bacteria Streptococcus equi causes strangles, which got its gruesome name from the fact that it can cause lymph nodes in a horse’s throat area to swell so much that they interfere with the animal’s breathing.

“It can be found in the environment, but we know a potential source is the guttural pouch of asymptomatic carriers—horses that are not showing clinical sign of disease but have the bacteria in their guttural pouch,” said Dr. Michele Frazer of Hagyard Equine Medical Institute. “It can be spread through contact, so through nasal secretions from one horse to another. In the past, we used to think it lived out in the environment for quite a while, but recent research shows that—at least outdoors in the environment—it doesn’t live more than one to three days, and, if there’s sunlight, it probably doesn’t live for more than 24 hours. In a barn, in an area that’s moist and not exposed to sunlight, it might live longer. So the way it spreads tends to be from horse to horse, from a horse that has the infection in its guttural pouch to another horse.”

The disease’s relationship to the guttural pouch also has another potentially serious ramification: infection of one or both of a horse’s guttural pouches can be fatal.

“Chronic infections in the guttural pouch can form chondroids,” Frazer explained. “Basically, the guttural pouch fills up with pus, and that pus over time will harden into little round things that look like marbles, and those are chondroids. Those can be very difficult to get out of the pouch. There are many important structures that run through the pouch, like cranial nerves and the internal carotid arteries, that can be damaged by the presence of those chondroids. And the chondroids are also serving to contaminate the environment.”

A case of strangles can itself prove fatal—swollen lymph nodes can compress the trachea, for example—but it is generally treatable.

“It’s feared because we don’t necessarily know which horses are infected, and it can cause pretty severe clinical signs,” Frazer added, “and once you have a horse that is visibly clinically sick, the disease can rapidly spread through a population of horses.”

You might not be able to identify an asymptomatic carrier, but there are clinical signs of strangles to watch out for.

Clinical Signs

Fever. “That’s just one more good reason to take your horse’s temperature every day and know what his baseline temperature is,” said Frazer. “If a horse spikes a fever, especially if that horse has been in an environment where they might have been exposed—like a show or somewhere else where they have mixed with other horses—then strangles should be on your list of possible issues.”

Nasal discharge.

Swollen lymph nodes.

“They don’t have to have all of these signs, and they don’t have to have the swollen lymph nodes,” Frazer noted. “Sometimes the lymph nodes will swell internally, so you can’t actually see the swelling. But certainly is you have a horse that has suddenly developed swelling in its throatlatch area, strangles should be on your list. When I get a horse in the clinic that has a fever with either nasal discharge or an acutely swollen throatlatch, strangles is on my list.”

Photo: AkaEmma

The incubation time—the time between when a horse gets infected and how long it can take before he shows clinical signs—can range from three to 21 days, if he shows any signs at all. “During that 21 days, that horse can spread it from one end of the barn to the other, into the wash rack, inside the riding arena, everywhere,” said Frazer.

There is a vaccine for strangles, but, as Frazer cautions, “No vaccine is 100% effective. A horse having been vaccinated for strangles is not a guarantee that they will avoid the disease if they’re exposed.”

Frazer recommends talking with your veterinarian about the vaccine and its likely effectiveness for your horse and his risk level before decided whether or not to vaccinate.

Diagnosing Strangles

Diagnosing strangles involves taking a nasal swab or flushing bacteria-laden fluid out of the horse’s guttural pouch (which typically requires an endoscope) and then either culturing Strep equi from it and/or testing the fluid for the presence of Strep equi DNA.

“Finding that horse who is a carrier sounds easy enough, but practically and financially it can be difficult,” Frazer said. “Generally, we want three to five cultures before we call a horse negative for infection, and that can get expensive if you have a barn full of horses and you’re going to do three to five samples for each horse. And it can be time-consuming.

“There are two tests,” Frazer added. “We can do a PCR, where we’re looking for the Strep equi DNA, or we can try to culture it. There are advantages and disadvantages to each of those. Typically, if I get a horse in the clinic that I’m testing, I run both. But if you’re managing a farm with a large population, then your veterinarian may choose one or the other from the economic point of view.”

To Treat or Not to Treat?

After diagnosing strangles, your veterinarian might suggest letting the illness run its course.

“Some people advocate not treating, unless the horse is severely compromised,” Frazer said, “and some people advocate always treating. There’s not necessarily a right or wrong here. In the case of a healthy adult horse, I might let the strangles run its course. If I have a very old horse or a very young horse, I’m going to treat it with antibiotics.”

If left untreated in an otherwise healthy adult horse, the disease generally takes a couple of weeks to run its course, Frazer said, and the horse might shed the bacteria for another couple of weeks after that. Not treating the infection in a horse that is likely to be able to fight it off will allow that animal to build up his immune system, and that’s one reason your vet might suggest letting a strangles infection play out without intervention.

“We also worry sometimes about giving a horse antibiotics and suppressing the bacteria but not entirely clearing it,” Frazer explained. “Then, when we discontinue the antibiotics, the horse can get abscesses in other parts of their body”—a rare condition often referred to as “bastard strangles.”

Fortunately, antibiotics are generally effective.

“Penicillin is usually pretty good at killing the Strep equi, so these horses can be treated with systemic penicillin,” Frazer said. “Trimethoprim-sulfa is not quite as great, but it’s decent at getting rid of it, so that’s another option for treatment. If the horse has a guttural pouch infection, then penicillin directly into the guttural pouches is the best option.”

Cleaning out the guttural pouch and applying antibiotics takes more than one treatment, Frazer cautions. “I’ve had horses who come in almost daily for several weeks,” she said.

Whether your veterinarian recommends treatment or not, it’s wise to test the horse after its recovery to make sure it hasn’t become an asymptomatic carrier.

Action Steps in an Outbreak

If a horse shows signs of infection, there are immediate steps to take.

1. Isolate the affected horse, preferably outside.

“You want to put that horse somewhere where they’re not going to keep spreading it,” Frazer said. “Ideally, get them outside, if weather permits and the horse isn’t too sick to go outside. If they can go outside, that’s ideal because the sunlight will kill the bacteria in the environment far faster than if the horse is inside. If he’s sneezing on adjacent stalls or if he’s going into the community wash rack and those kinds of areas, it’s harder to disinfect it.”

2. Keep separate equipment for affected animals.

Keep any equipment related to the affected horse—such as brushes, buckets, and pitchforks—separate and use them only for that individual animal. If you can’t house the horse outside, it’s also a good idea to clean its stall last and then disinfect the pitchfork to help lessen the chances of spreading bacteria.

“When cleaning the pitchfork, be sure you get all of the fecal matter off, because a lot of disinfectants are great at killing the bacteria, but they do not work if there is fecal matter stuck to the surface,” Frazer said. “So clean it first, then disinfect it and leave it in the sun.”

For more information on biosecurity protocols and best practices, see US Equestrian’s online brochure, “Biosecurity Measures for Horses at Home and at Competitions.”

3. Disinfect.

“It’s not all that difficult to clean the environment. It’s frustrating, and it’s a maintenance and management issue. But it’s not difficult to kill the bacteria; many of the routine disinfecting agents that you clean your stalls with are going to get rid of it.”

For more on disinfecting stalls, feed tubs, and water buckets, check out this article.

“But the harder issue is clearing it from the horse population, because you don’t know which of the horses could be a sub-clinical carrier of the disease,” Frazer said.

4. Do NOT vaccinate during an outbreak.

“If a horse has been exposed to strangles and it’s then vaccinated, they can develop a completely different disease called purpura hemorrhagica, and in many ways that can be worse than the strangles,” Frazer said.

5. Shut the barn to traffic.

“Basically, shut the barn down if you can,” Frazer said. “Stop traffic in and out, and limit the people who walk around.” Limiting human and equine foot traffic can help prevent the bacteria from spreading.

“The horse owner who pets their horse and gets covered in nasal secretions and then goes down the barn aisle petting other horses or sticks their arm into a communal feed bin can spread the bacteria along the way,” Frazer explained.

6. Be aware of your state’s reporting requirements.

“Depending on what state you live in, strangles may be a reportable disease,” Frazer said. If it is a reportable disease in your state, your veterinarian must notify state animal health officials. This notification is a legal requirement in some states; consult your veterinarian for details. You can find a list of each state’s animal health officials here.

Horses who have had strangles should, in theory, be less likely to come down with it again. “They should have decent immunity to it, but that’s not a guarantee,” Frazer said. “As far as property goes, if it’s been disinfected properly and there are no asymptomatic carriers left there, then they would be no more likely to get it again. But places do tend to end up with asymptomatic carriers, and that’s why some farms can feel like they end up with a lingering issue. It may seem like it’s in the environment, but chances are it’s in a horse.”

An Ounce of Prevention

There are preventive steps you can take to head off a strangles outbreak before it ever happens. Good biosecurity protocols at home and on competition grounds or when traveling are key.

“Have a clean environment,” Frazer said. “If you’re going to a competition environment, try to keep your area clean from other horses and their secretions—for example, make sure your horse is not using the same water bucket as his neighbor. At a boarding facility, when a new horse comes in, isolate that horse for a period of time to make sure they don’t show clinical signs of illness or even consider testing that horse.”

Disinfecting trailers that have brought new horses onto a farm or have returned from a show is also a good practice.

“The bacteria can spread through shared pitchfork, rakes, and that type of equipment, so if you’re at a show facility, don’t share those items,” Frazer said. Horses who show any signs of illness should have their own dedicated equipment.

For more information on isolation protocols and other biosecurity practices, see US Equestrian’s online brochure, “Biosecurity Measures for Horses at Home and at Competitions.”

Another good practice, Frazer said, is to combat continuing wetness. “You want to dry everything to prevent the bacteria from hiding in damp places like the wash racks,” Frazer said. “In areas where there’s continued moisture, like the wash rack or corners of stalls that might not thoroughly dry between cleanings, you want to try to dry those places out.”

Want articles like this delivered to your inbox every week? Sign up to receive the Equestrian Weekly newsletter here.

This article is original content produced by US Equestrian and may only be shared via social media. It is not to be repurposed or used on any other website than USequestrian.org.